PFAS in the Coosa: A Breakthrough Year for PFAS Research

PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are a class of man-made chemicals used in everything from non-stick cookware to firefighting foam and water-resistant materials. Known as “forever chemicals” because they don’t easily break down in the environment, PFAS compounds can accumulate in our waterways, wildlife, and even our bodies posing significant risks to public health, including increased risk of cancer, liver damage, hormone disruption, and developmental issues. That’s why, for the past few years, we’ve been focused on better understanding how PFAS moves through the Coosa River Basin and what we can do to protect our communities from exposure.

Our PFAS monitoring journey began in 2023 with a national pilot study led by Waterkeeper Alliance and other Waterkeeper groups around the country. This was our first glimpse into just how prevalent PFAS contamination could be in our own watershed as well as the rest of the country. Although a small sample size, the results showed the Coosa basin being the most contaminated in Alabama, and one of the top in the country.

From there, we knew we needed to dig (or swim) deeper. Our second large-scale PFAS project was a collaboration with the Coosa River Basin Initiative, where we took 65 samples spanning the entire Coosa River Basin. The results were sobering: more than 80% of our samples tested positive for multiple PFAS compounds. This wasn’t isolated. This was widespread.

That study confirmed what we feared; that PFAS contamination is persistent, mobile, and under-monitored. It also laid the groundwork for our long-term strategy: keep building a robust, Coosa-specific PFAS dataset that could help us push for stronger policies and more stringent protections from state and local agencies while also allowing us to educate the folks that it will and has continued to effect.

Meaningful action starts with data. If decision-makers aren’t going to collect that data themselves, we’ll keep doing it sample by sample. In 2024, we expanded our PFAS efforts significantly by participating in three different studies, each with a unique approach to testing and a shared goal: to increase understanding of PFAS movement and detection in the Coosa River Basin.

|

|

|

| “It’s deeply unnerving to me that a perfectly clear glass of water can have thousands of times the safe limit of PFAS, it’s disheartening to see how widespread the contamination is, and exhausting to continually uncover it. But I’m deeply grateful for the folks that continually push the needle forward in regard to creating new detection methods, better technology, and of course letting waterkeepers do more field work in the name of progress.”

– Lucas Allison, Field Director |

|

|

| Study 1: Tracing PFAS Through the Dams (Cyclopure Round 2)

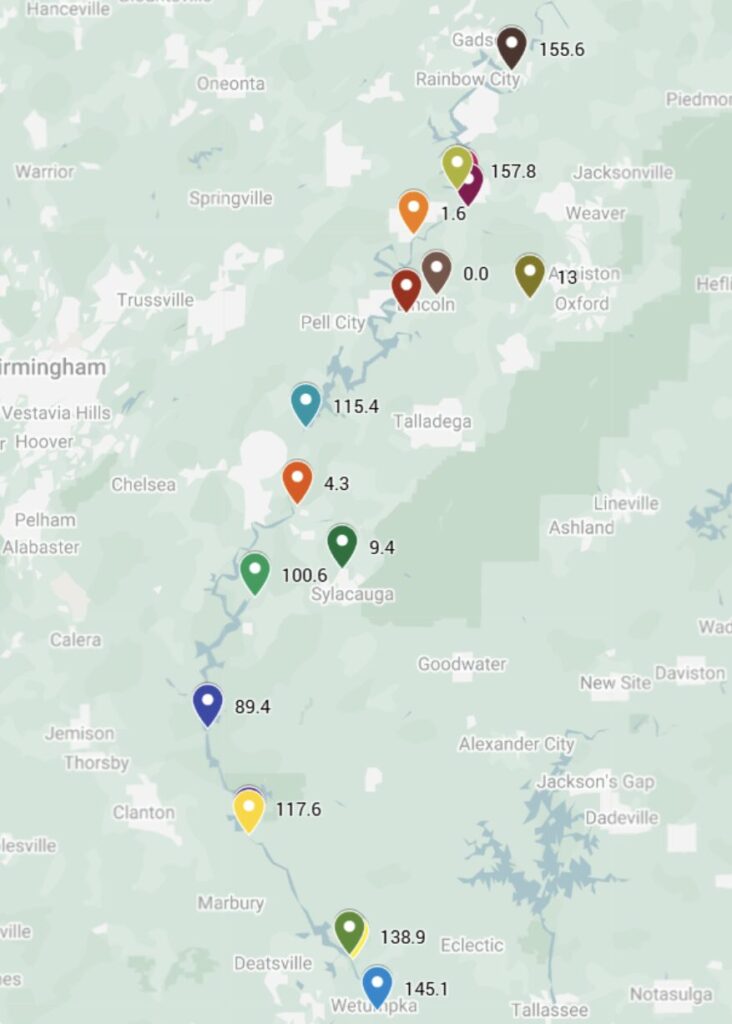

Partnering once again with Cyclopure, we conducted a focused sampling effort to investigate how PFAS moves through the Coosa’s five main reservoirs: Neely Henry, Logan Martin, Lay, Mitchell, and Jordan. Using Cyclopure’s established detection method, we took 15 single-timeframe, one-cup samples from locations above and below each dam.

Our goal was to determine whether PFAS levels changed from impoundments to tailwaters and if dams and water infrastructure might influence how these chemicals are distributed downstream.

The results showed PFAS contamination both above and below each dam, with slight increases in concentration downstream in some locations. While more data is needed to confirm a definitive pattern, this raises important questions about the role of infrastructure itself. Grease-resistant components, oil runoff, or other industrial compounds embedded in dams could be influencing PFAS levels. These findings point to the need for deeper analysis and more regular sampling in tailwaters.

|

| Study 2: Long-Term Detection with Submerged Samplers

The second study took on a brand-new PFAS detection method designed to observe chemical accumulation over a 30-day period, rather than just a snapshot in time. We were provided with four specialized sampling cages, each fitted with a series of vials and semi-permeable membranes that would slowly filter the surrounding water and capture PFAS compounds over the month-long deployment. But first, we had to solve a seemingly simple challenge we’d never faced before: how do you keep scientific equipment submerged and undisturbed for 30 days in two different creeks?

For the shallower site, we got creative with rebar, zip ties, and a good amount of elbow grease, securing the cages directly to the creek bed. The deeper site, around 20 feet deep, required a more inventive solution: we built our own 15-pound concrete anchors using buckets, eyebolts, and quickcrete. Using steel cables, an empty air-sealed water jug as a buoy, and a steady canoe, we suspended the cage at mid-depth in the water column. It was equal parts engineering and improvisation.

Thirty days later, we returned (by canoe) and found the cages exactly where we left them. The samples were packed and sent off to an external lab; proof that even the most experimental methods are possible with a bit of ingenuity and redneck engineering. Results should come out soon.

Study 3: Beta Testing Instant Detection Technology In our third PFAS study of the year, we helped beta test a brand-new detection technology that could eventually allow real-time field testing of PFAS, no external lab required.

Currently, most PFAS testing requires large-volume water samples and weeks of shipping followed by lab analysis. If this new technology succeeds, it could radically streamline how we monitor our rivers.

For this beta test, we were asked to collect three 10-liter samples from sites with known or suspected contamination and ship them to the developers for testing with their prototype. Simple enough in theory, but those sample boxes were heavy, and international shipping proved to be a logistical nightmare.

The first batch never made it to the lab, forcing us to resample the same locations. The second attempt, where we shipped samples separately, had better results. Two of the three arrived successfully, which was enough to continue. We didn’t get our hands on the new device this time around, but we’re hoping to be part of Phase 3 of the project and bring this tech to our watershed as soon as possible.

What’s Ahead: Fish Tissue and More As we look to the rest of 2025, we’ve got even more PFAS work on deck. Next up, we’re planning to collect fish tissue samples from key spots around the basin. The goal: determine how much PFAS is accumulating in species that anglers commonly catch and eat.

We’ll also be continuing our work with Cyclopure and supporting further development of the real-time detection method. Every study, every sample brings us closer to a clear picture of PFAS in the Coosa and to the policy changes needed to address it. Because clean water isn’t just about what you can see, it’s about what’s in it. And until “clean” means truly clean, we’ll keep testing. |